Governments and companies alike depend on international trade data for reliable statistics to track the ever-shifting marketplaces for traded goods. Because the sources for this type of data are official government statistics offices, this data represents one of most trusted means of gauging import and export activity between countries for individual commodities.

However, governments also have a vested interest in balancing the mutual aims of accuracy and transparency with the sometimes competing needs to protect its own citizens and economy. Toward that aim, governments sometimes employ practices known as statistical confidentiality or suppression schemes to mask the reporting of some otherwise important data, limiting observers to a less than complete view of the marketplace. While there are various methods employed to execute such intentional obfuscation, there are also strategies observers can use to approximate the true nature of trade despite these data limitations.

Trade data confidentiality schemes exist because ongoing publication of the data in question has security implications or would cause a competitive disadvantage to parties involved in the trade. For instance, if there are only two exporters of a particular good in a particular country, the government's (referred to as the "Reporter" of such data) publication of the total export trade figures for that good would allow both of the parties involved a window into the business of the other venture. Competitors could simply view the overall trade volume and/or value and subtract out the portion of their own business, thereby giving them a view into the amounts of goods exported, foreign export markets (referred to as the "Trade Partner" of such export data) and even the average price that they are receiving for those goods. This type of transparency can be viewed as putting affected companies at a competitive disadvantage, so governments may employ confidentiality schemes where some or all the details of the trade of certain goods are not reported.

International trade data is published using the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS or HS) classification system which assigns a particular code to every traded good commodity in a 2-digit chapter system ranging from 01 through 99. The granularity of goods increases as the HTS digits increase, with 2-, 4-, and 6-digit codes and associated definitions acknowledged universally across all the world's reporters. Reporters are also able to define their own specific tariff-line codes that exceed six digits, such as at the 8- or 10-digit level for maximum commodity granularity.

Confidentiality schemes take different forms according to the practices of the reporters involved. Some common variations are as follows:

As effective as these suppression schemes may initially seem, there is an important limitation: they are only applied to the data sets of the reporters in question. These same reporters have no control over the data reported by their trade partners, who do not share the same concerns and considerations as the reporters applying their own suppression schemes, which leads to a gap in those schemes' effectiveness. This gap can be exploited by savvy trade data users to better understand the true trade activities despite the presence of suppression schemes.

The power of these workarounds is because, most often, these trade partners are also independent reporters in their own right. In other words, when Australia reports the export of iron ore to mainland China, Australia is the reporter and mainland China is the trade partner. Although Australia can and does invoke whatever suppression scheme(s) it desires, mainland China also publishes its own trade data independently that aims to capture the imports of iron ore from Australia in a so-called "mirror trade" view. In that latter example, mainland China is the reporter and Australia is the trade partner. Mainland China does not share Australia's suppression schemes, although it may employ alternate suppression schemes itself.

Having access to an international trade platform that captures a large number of reporters is key to this type of analysis. The Global Trade Atlas by IHS Markit provides monthly world trade statistics for 102 reporters representing over 98% of world trade and all traded goods commodities, making it easy to pivot between reporters and trade directions to access different reporters interchangeably for the same commodity of interest.

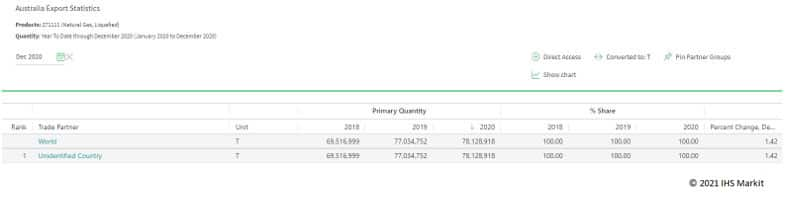

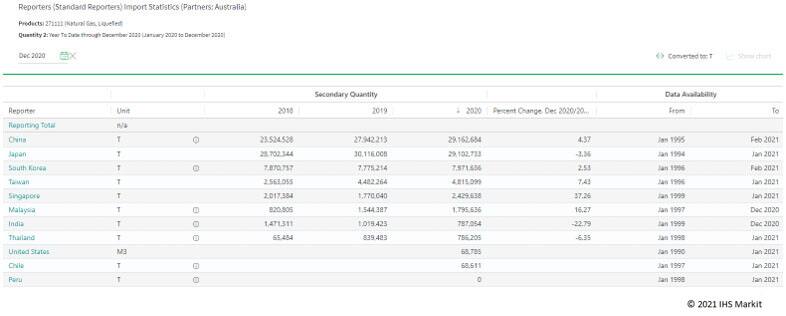

One example of a suppression scheme at work is that of the Australia government, who for years have used a confidentiality scheme to eliminate some or all the details of the trade of certain goods from the information they release. A prime example of this is liquefied natural gas (LNG), a commodity for which Australia became the number one exporter of in the entire world in 2020. Seeing where Australia is exporting to and how much they are selling into those markets could be a valuable piece of information, but LNG exports fall under the Australian government's confidentiality scheme resulting Australia masking the specific export destinations for LNG, but not the overall quantity.

Trade data users limiting themselves to a view of Australian exports for LNG find themselves without a view to where the goods are being exported, but access to a greater range of trade statistics helps circumvent the national confidentiality scheme. A review of what all other available reporters have published for imports of LNG from Australia provides us with a proxy list of export markets for this product.

Analysis shows that using this method accounts for 98.5% of the total exports from Australia in 2020, providing a high degree of confidence that this method has almost fully captured the total market and successfully circumvents the confidentiality scheme in place.

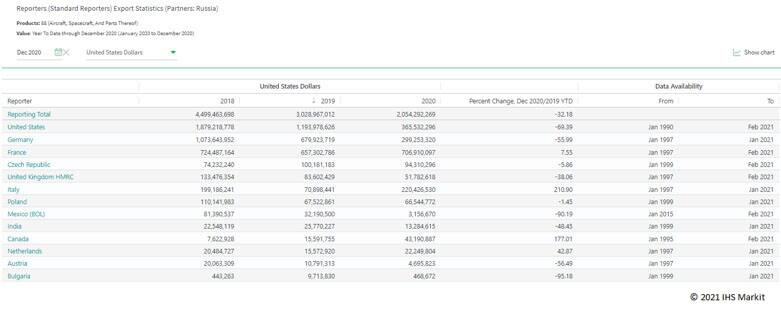

In other cases, the scope of the coverage offered by using other trade statistics is less easily gauged. A search of Russia trade statistics reveals that the export and import of aircraft & their parts (HS 88) are totally excluded in the reporting.

While the mirror trade example below captures slightly over $2B in total exports to Russia, there is no way to estimate how much of the total imports have been able to be accounted for due to Russia's complete suppression. This method can, however, still be used as a barometer for the market size and activity even if it cannot be corroborated by the reverse trade direction.

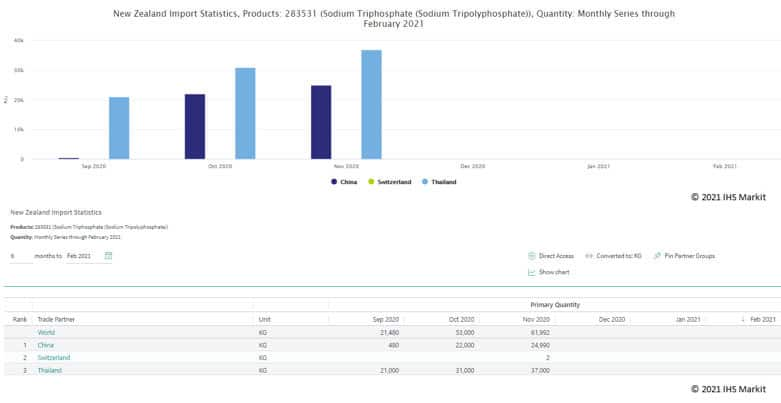

While some nations have their suppression/confidentiality schemes as an ongoing process, others set time limits on the suppression of data. New Zealand has a staggered approach to their confidentiality scheme, setting either a 3-, 12-, or 24-month period around suppression. At the end of the period, those affected by the suppression are contacted by Statistics New Zealand and, depending on their feedback, the suppression may either continue or cease. However, in the world of international trade, three months can make the difference between useful business intelligence and just data, so users again can turn to the statistics of the other reporters to fill in the gap.

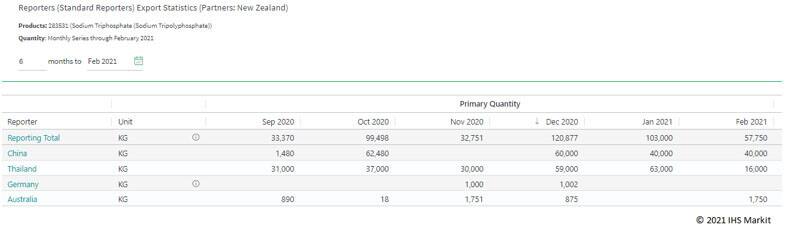

For instance, a review of sodium triphosphate (HS 283531), a food preservative, shows a 3-month confidentiality lag on its imports into New Zealand:

Though data for New Zealand is released through February 2021, the reported data for this particular commodity ends in November 2020.

However, producing a mirror trade view of exports of sodium triphosphate destined for New Zealand, the gap in data is easily overcome, allowing users to circumvent the confidentiality scheme that New Zealand employs, especially by corroborating to the known data published November 2020 and prior.

In conclusion, despite international trade being generally well-documented in our globalized economy, it is not entirely exempt from intentional obfuscation as governments strive to balance the needs of the specific market participants. A creative approach to the available data can help observers to overcome data limitations, such as in the case of suppression schemes and statistical confidentiality that exist now, or ones that may be deployed unexpectedly in the future.

Posted 10 May 2021 by Russell Patterson , Subject Matter Expert, Maritime, Trade & Supply Chain, S&P Global Market Intelligence